The Fortnightly Interview: A Good Memory Is a Friendly Ghost

Henry Carrigan in conversation with poet Maggie Smith

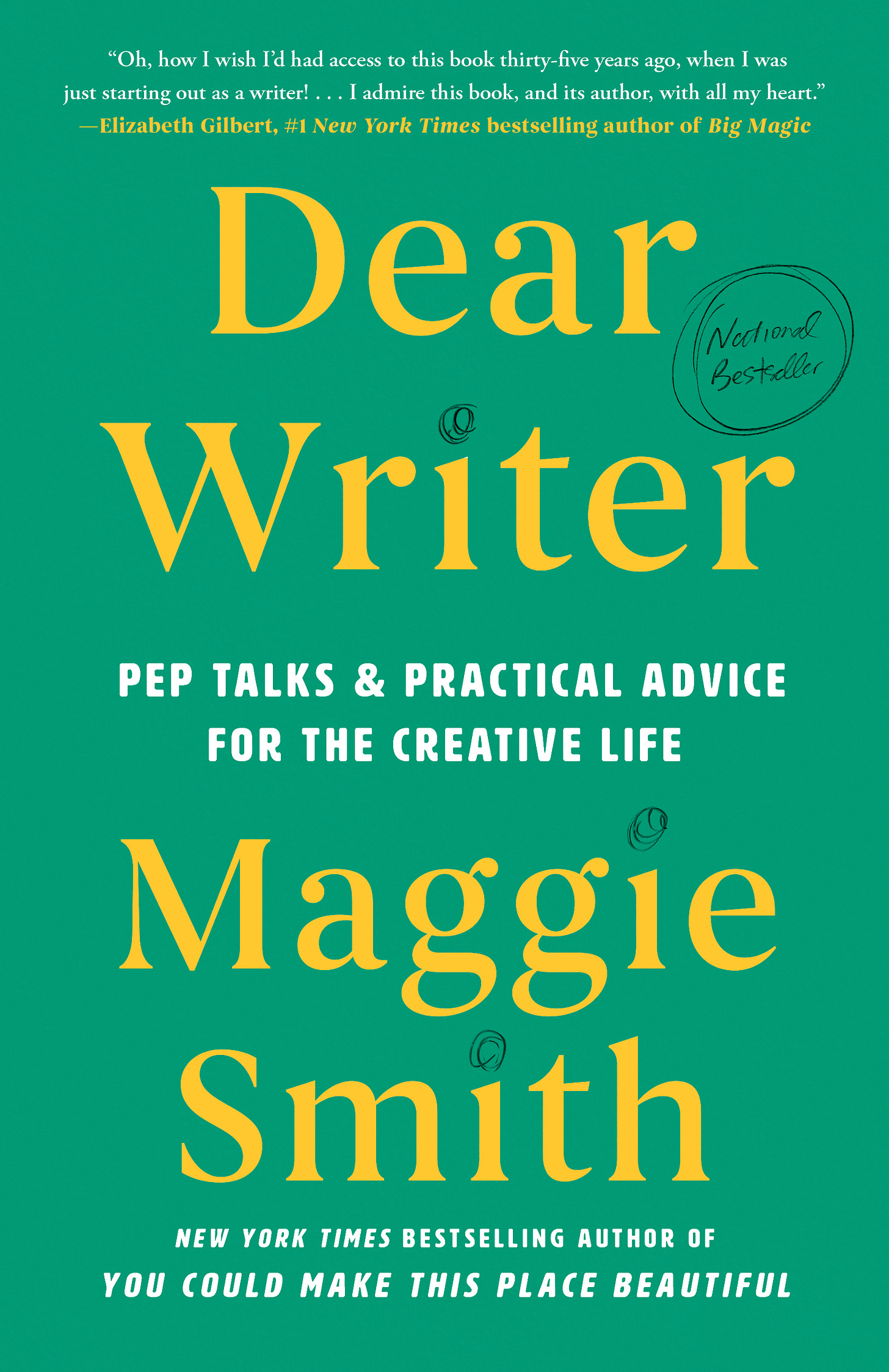

In her new book Dear Writer: Pep Talks & Practical Advice for the Creative Life (Washington Square Press/Atria), award-winning poet and memoirist Maggie Smith (You Could Make This Place Beautiful; Good Bones) draws on her over twenty years of teaching, editing, and writing to offer practical advice to writers at every level of experience. Smith breaks down creativity into ten essential elements: attention, wonder, vision, surprise, play, vulnerability, restlessness, connection, tenacity, hope. Each section opens with a short “dear writer” letter that calls attention to the element she explores in that section. Following her opening missive, Smith explores three facets of that creative element, plucking exemplary lines and stanzas or complete poems from her own oeuvre; thus, in her section on “restlessness,” she reflects on constraint, restraint, and revision as key components of restlessness. Smith then closes each section with writing prompts, and a list of further reading, that writers can use to inspire and motivate them.

The Fortnightly Review chatted with Smith recently about her new book in a wide-ranging conversation that covered music, artificial intelligence, and creative writing. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Henry Carrigan: Can you tell me just briefly the story of the book, Dear Writer: Pep Talks & Practical Advice for the Creative Life? Why did you decide to do it now?

Maggie Smith: It's actually sort of interesting. I wrote a draft of this book before I wrote my memoir, so this was the book to follow Keep Moving and my next book of poems, Goldenrod. When I decided to write the memoir, we kind of pressed “pause” on this book and said that book should come first. So, when I came back to the draft of Dear Writer after publishing and touring on the memoir, I was like, no, that's not the book I would write now. I would write a completely different book now, three years later. So I got permission from my editor to start over, and I wrote a completely different book.

I think it's funny because I talk so much about revision in this book, like not taking anything for granted; every time you look at something, everything is up for grabs. I really walked the walk with this book because I ended up rewriting it! When I came back to it I thought: I really want this to be more useful for people and actually less about me now that I've written this memoir and more about resources to help people who are either getting started or maybe have fallen off the writing wagon a little bit or are feeling a little stuck and want to kind of re-enter that space. So the structure of the ten elements came up in that second draft.

HC: I can see this as an ideal book for a creative writing course.

MS: Oh, that makes me smile. I think I received Anne Lamott's Bird by Bird when I graduated from high school, so I was probably eighteen years old when I first read that book and highlighted the heck out of it. To me, probably because it was the first craft book I ever read, it was sort of the gold standard in my mind of what a craft book could do, how specific it could be and also how human it could be and self-deprecating. Like, “I am not speaking to you as a wise oracle who has this all figured out. I am speaking to you as someone who is still grappling with these things on a daily basis.”

HC: Picking up on your notion about revision, you've also been an editor and you also work as an editor. How do you balance those roles just moving from working on, say, a manuscript and then going back to writing your own writing. How do you balance that? What's the balance? Is there a balance?

MS: I think most writers cobble a living together doing various things, right? Most of us teach in some capacity or do public speaking, or edit, or...I mean, frankly, we're doing all kinds of things.

It's not difficult for me to toggle so much between these different modes. It’s more about how do I reserve the best of me for my creative work and how do I budget my time to do that? I know that my kind of generative engine brain is good the first thing in the morning and it’s sometimes good again very late at night. So knowing that about myself I try to do all admin, including emails, mid-day because it’s not the time where I’m baking poems as efficiently. (laughs)

HC: Do your late nights and early mornings ever meet each other, like a musician?

MS: Not that much anymore. I think I'm too old for that, but I mean, probably in my twenties they did, you know, like writing in the wee hours of the morning. These days not so much. I find that kind of liminal space—like first thing in the morning before the day has had a chance to really get at you and you’re coming out of a kind of softer mindset and then the same thing end of day, when people aren’t reaching out any more and things are settling down and you’re heading toward that dream state—those two kinds of little hallways, out of sleep and into sleep, could be good hallways for poems.

HC: Can you talk a little bit about the interplay between freedom and constraint, or idea and form, in poetry?

MS: I think I quote this in in Dear Writer, but it's something I think about all the time. The poet Terrance Hayes was speaking to a group of high school students; I think this was around the time he was writing his American Sonnets [for My Past and Future Assassin]. One of the students said, “Why do you write in form. Like, you can do whatever you want. You’ve written tons of free verse poems, why are you doing this?” Why impose a constraint upon yourself? Why build yourself a cage? He said something to the effect of: well, it’s pretty cool if you can breakdance but it’s even cooler if you can breakdance in a straitjacket. And I love that metaphor because it’s exactly what we do as poets. I’m not in class anymore, no one is telling me I have to write a sestina; so why would I choose to write a sestina, write a sonnet, attempt a specific kind of lyric essay? Why would I even give myself any kind of constraint because if no one’s grading it there’s no rule?

If I give myself some constraints, it forces me to be more creative in other areas. When I’m writing a prose poem, I feel like I’m writing with one hand tied behind my back, and I can’t lean on line breaks for meaning or pacing and so what do I have to do to make up for the lack of that thing? I mean, frankly, why am I writing it as a prose poem if I feel like I have one hand tied behind my back? (laughs) I can write everything in couplets because that’s my favorite. But there’s something about having to skip over first thought/best thought and get to a place that’s a little bit more challenging and rigorous, and it’s like the good kind of hard. I like that poems are still hard for me to write; they’re still challenging and part of why they are still challenging is because I make rules for myself about what I’m allowed to do.

HC: When you start writing do you start with an idea or a form?

MS: I think in fiction they call it plotters or pantsers: either you plot or you go by the seat of your pants, and I’m completely a pantser.

I work pretty much on legal pads or in notebooks at first. Then a poem starts to kind of tell me what shape it wants to be; I can kind of sense, oh this is about the length of the line, or based on the beginning I think it’s gonna to be in quatrains. As soon as I start having a conversation with myself about form, I’ve outgrown the handwritten draft and then I will put it into a Word document and start to kind of see how it looks on the page and move around and cut and paste and try out a bunch of different things. It never really has a shape at first, not until I am able to get it into the document and see what it might want to do.

HC: So I'm using a musical metaphor here, but do you see yourself as writing singles rather than albums?

MS: Oh, yeah. It’s funny; putting together a book often feels like putting together a playlist or a record, right? It’s all of these things and how they are in conversation. I guess some books are more like concept records where they really do feel like they hang together thematically—the project book, as we sometimes call it. Some books are more wide-ranging and they’re almost more like a greatest hits: like these are the poems I‘ve written over the past five years that I really like and I think I’ve arranged them in a way that lets them live between two covers. But, yeah, I write one poem at a time typically without having any idea of what the book will be when it becomes a book. So I like to say that I’ve published five books of poems but never written a book of poems. Because I just write one poem at a time and at a certain point I’m like “I think I’ve got enough for a book and then I print it all out and see what I’ve got.”

HC: So you must leave some on the studio floor, too.

MS: A ton! With Goldenrod, my last book of poems, I had a residency at the University of Arizona Poetry Center. I printed out all the poems that I had written since my book Good Bones came out, and it was like 130-some poems in my suitcase. And I think Goldenrod has 52 or 54 poems in it, so there's almost always like double or three times as much what I need.

HC: You have a great sentence in the book about repetition. You write that “the magic trick of repetition is that it enacts remembering. . .and memory is a kind of haunting.” Can you talk about that? About memory and haunting and repetition as being an act of memory?

MS: I think anytime you're using repetition in a text, you're playing with memory, because once you see something two or three times what you're counting on is the reader’s remembrance of having seen that before. I think it's part of why I love having a series of poems. I think all of my books have at least one series. I like to spread out the series rather than have them come in compartmentalized sections because I like the patterning of it. Then the reader gets to have an act of remembering the previous iteration, which is kind of stolen from them when all of them are stacked together. To me there's a pleasure in the recognition of something. I think our human brains really enjoy pattern recognition. And so, when we see something that we've seen before, it's like, oh yes, and it also kind of makes us feel capable of moving through the text because we are recognizing a pattern. And we're like, oh, we get this, we're going the right direction. It's like a signpost.

I think I really came upon this when I was working on my memoir, which is how much memory is a haunting, and a good memory is like Casper, right? A good memory is a friendly ghost that lives with us. And whenever we think of it, it's like, “I'm so glad I've got that with me, that kind of companionship of that friendly memory.” But a bad memory, that kind of nightmare memory is like a bad poltergeist, (laughs) right? Moving around things and sneaking up on you and yanking your ankles from under the bed in the middle of the night. And so how do we use that in a piece of writing? Repetition can work in different ways, depending on the tone and the content of the piece, so getting a refrain about something that's like warm and nostalgic and loving is a very different use of repetition than bringing up something where you can tell the speaker or narrator is like pained or ruminating, or wishes they could sort of exorcise—to continue the metaphor—this thing from their life. I think I'm somebody who replays things often in my mind, good or bad, and so it's really natural for me to use a lot of repetition in my work.

HC: This also raises the notion of cross-pollination, which you bring up in your section on connection. Can you talk a little bit about the role of cross-pollination and art in general and in poetry? Linda Ronstadt once told me that she loves to sing with a book of art open on the music stand in front of her.

MS: I love that. It's almost like synesthesia, like having some sort of visual representation of art that then informs your vocal performance. I find that really interesting.

I think I'm kind of like a magpie, which is funny because it was one of my nicknames as a kid. I'm always collecting little things and finding ways to use them in my own work. A lot of times people will ask how can you listen to music and write at the same time, because I do; I listen to music constantly and with lyrics. It doesn't bother me to write kind of through that noise, and actually sometimes it's almost like a river, like a current, and it kind of picks up sediment and rocks as it moves. I'm sure that listening to music as I'm writing I'm picking up things as I'm moving through it. And I love that. I mean, there's a reason why one of the assignments I give almost every time I teach in a classroom or an extended workshop is an ekphrastic poem. There's a reason why I encourage students if they want to write a cento to not only consider lines of poetry, but maybe to consider writing one from song lyrics. I just think all of us, whether we are really cognizant of it or not, are constantly picking up frequencies from other art forms. It's really interesting that a lot of people seem to believe cross-pollination could be dangerous for your work. Like, if I'm writing a novel I shouldn't be reading novels, or if I'm writing music, I don't want to be listening to music, because what if I accidentally incorporate too much of that voice or melody? I actually think the opposite is true: the more we engage with other people's art, it's sort of like art begets art begets art. It helps us make things, and then we could make something that then would maybe inspire someone else. It's this giant kind of chain, really, that we shouldn't feel ashamed of taking part in.

HC: Well, it also gets your notion of community too, because that is a way of making community, right?

MS: I even think of books as sort of community gathering spaces, right? Like you could meet somebody who's read something that you've read or likes a band that you like or seen a movie that you've seen. And suddenly, even if you're complete strangers, you have this world in common. And I love that.

HC: Do you have any thoughts about the relationship between creativity and artificial intelligence or generative AI?

MS: You know I do. (laughs)

I do have some ideas about that. I guess what I would say is I'm very glad not to be a classroom teacher right now. First of all, I mean, I have a sixteen-year-old and a twelve-year-old. And they're like, “Oh yeah, a lot of kids are using ChatGPT to write their essays, and then the teachers have to run it through a software.” So, unfortunately, it's turned a lot of teachers into just sort of, like, original-thought police, where you basically just have to be scanning your students’ work or requiring them to write in composition books in class rather than giving them work to take home with them so that they're forced to think in real time, without a device. It makes me nervous.

A few years ago, when my memoir came out, I did a podcast episode with Kara Swisher. She said while we were recording—and I don't think it made the episode—she asked, I think ChatGPT, to write a poem in the style of Maggie Smith. So it generated this poem. I could tell after she read it that it was pulling not only from my poems but from interviews and probably book reviews like just generic sort of ideas about what I do. It was terrible. We laughed, and she said, “I think you have job security here because AI can't actually do it.” And of course it can't. Creativity is about original thinking. It's called artificial intelligence; it's in the name. We need people who can imagine and hope and dream and love and suffer. I just don't understand how anything could be art if it's not created by a being that can do all of those things, and maybe that makes me old fashioned, but… (laughs)

I mean, I get it. I do. I have teenagers. Both of my kids like to write, which is good.

But when I was in high school, if there had been a ChatGPT for Algebra, I would have used it in a heartbeat, I'm sorry. (laughs) I realized that what I find sacred is art, including literature. And so, I am personally offended by the idea that people would not want to think for themselves, because that's what making art is. And yet, when I have found things incredibly difficult, I can also understand the desire to not fail your freshman English class or not get a “D” and let your GPA be tanked. And so having this shortcut that was not available when I was their age, it would be incredibly tempting. Just like when I was young, you know, you could pay someone to write a paper for you. Now they don't even have to do that; it's free and fast.

It's incredibly dangerous because part of what we're doing when we teach writing is teaching people how to think: not what to think, but how to think better. I think better on the page than I do off of it and writing has improved the quality of my thinking. If you're not willing to think on the page, you're going to suffer in other areas too, I think.

HC: What are some of the key challenges to poetry or being a poet or becoming a poet in today's world?

MS: I think I could answer that question in two different ways, which is how is it challenging to write poetry and be a poet and then the other thing is like how does one make a living? And the answer to the second question is like, most people don't, right? I mean the biggest barrier to being a poet in that regard is capitalism. Because poetry exists largely on the outside of it, which is what makes it wonderful. But it's also what makes it challenging. The best thing most people can do for their writing—and I say this as someone who now makes a living for my writing so this is going to sound a little disingenuous, but I mean it—is not make it their job. Just allow it to be a thing that just gives you pleasure and keeps you in touch with yourself. I think if people—whether they're just starting out or have been doing it for many, many years or maybe have started and fallen away—are thinking, “Okay, how do I make a living at this?” they will end up likely frustrated because that's poetry. But if your goal is to write, because that's what makes a writer, then there are very few barriers. I joke all the time that when I was a kid, my sisters played soccer, and it was very expensive for my parents to have them on traveling teams. And I always wanted whatever they spent on my sisters deposited in my bank account every month because I just required pens and paper. Writing is not expensive. You don't have to travel some place to do it. I don't need oil paints, I don't need canvas, I don't need a guitar. I don't need an amp; all I need is a legal pad and some pens, right? So, in that regard, there shouldn't be a lot of barriers. But when we start thinking about it in terms of publishing or making a living off of it then there are lots of barriers, and those barriers are not getting smaller, given what's happening with the arts funding in this country.

HC: What do you want readers to take from this book?

MS: Honestly, I think what I hope people get from this book is what I hope people get from most of my books, which is feeling a little less alone and feeling a little braver or less afraid. I think in this book it's about permission—to try, and fail, and know that other people, regardless of where they're at in their art or in their career, are also trying and failing. I think that kind of commiseration also helps us feel less alone in our own struggles in an art form and it helps us, I think, feel a little braver and willing to take risks and try new things. That's what I hope.

Maggie Smith is the award-winning, New York Times bestselling author of eight books of poetry and prose, including YOU COULD MAKE THIS PLACE BEAUTIFUL, GOOD BONES, GOLDENROD, KEEP MOVING, and MY THOUGHTS HAVE WINGS. A 2011 recipient of a Creative Writing Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, Smith has also received a Pushcart Prize, and numerous grants and awards from the Academy of American Poets, the Sustainable Arts Foundation, the Ohio Arts Council, the Greater Columbus Arts Council, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She has been widely published, appearing in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The Nation, the New York Times, the Atlantic, The Best American Poetry, and more. You can follow her on social media or find her online. Smith is also the host of the poetry podcast The Slowdown.

Henry L. Carrigan, Jr. teaches literature and creative writing at Lake Forest College. His interviews with authors appear in Publishers Weekly, where he writes about books. He also writes about books for BookPage, and he writes about music for No Depression, Folk Alley, and Living Blues. He has written about books for the Washington Post Book World, the Christian Science Monitor, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and the Charlotte Observer, among others.

So Far This Month in The Fortnightly Review:

Elegies on Brambles: On Jennifer Moxley, Stephen Rodefer, and Poetic Grief

Jennifer Moxley’s 2014 collection of poetry, The Open Secret, includes an hilarious and sorrowing versified Deaths of the Poets entitled ‘R.I.P.’ recounting the many ways in which poets have met a bad end before memorializing, perhaps sardonically, one who ‘died contented in a comfortable bed’. A year after