Recollection, but Not in Tranquility: On Desmond Egan

Donald Gardner reviews Desmond Egan's Laptop

‘Laptop’, poems by Desmond Egan

The Goldsmith Press, 2024 / 88 PP. £ 15 / € 20 /

ISBN 1870491 88 2

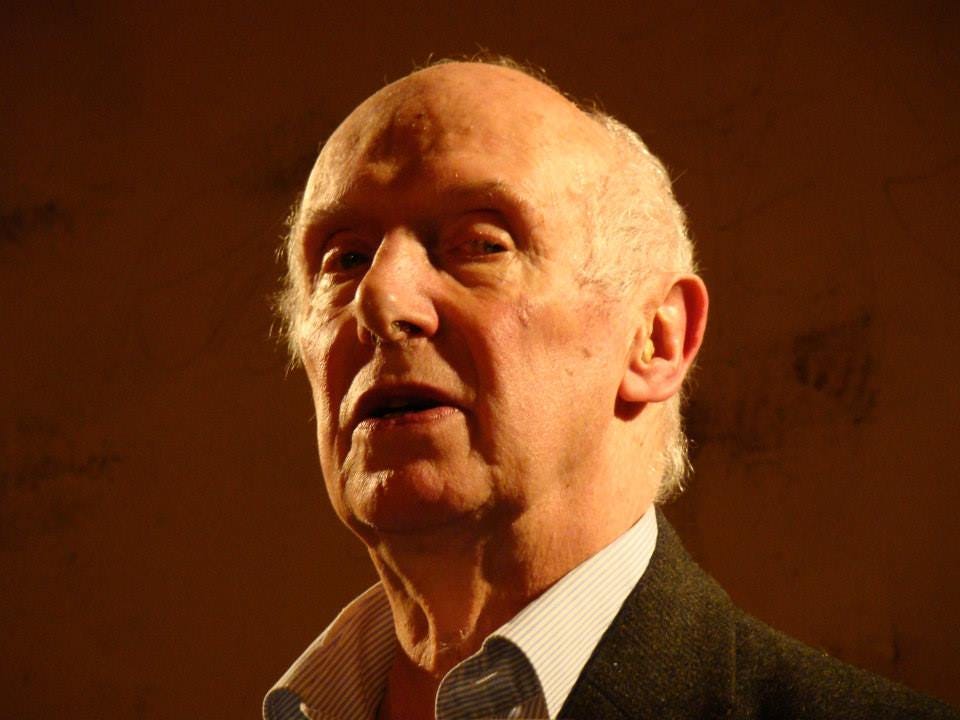

Review by Donald Gardner

Desmond Egan has published 24 books of poetry, and he is also the artistic director of the Gerard Manley Hopkins International Festival, held annually, in Newbridge, Co. Kildare. Now in his eighties, Egan was brought up in Athlone town, in the Irish Midlands. His new book ‘Laptop’, with a reproduction of a painting by Mark Rothko as its cover, draws attention to what one might call the miraculous in everyday life. His poem about Rothko is a good example, stating, as it does, his affiliation with the American abstract painter who explored mystical themes through his deployment of colour and coloured surfaces: ‘where the spirit bows / as in a sanctuary where / silence is glowing’. Egan’s use of synesthesia here, as elsewhere, provides an entrance to a world that, as he understands it, gives a meaning to life.

The core of ‘Laptop’ is a long sequence called ‘Memory Village’. ‘Plop of a fresh egg into /the bubbling saucepan / the tang of soda bread / of such is memory.’ Or: ‘only one bridge remains / gouged out of the cliff face / above a ferocious Atlantic / charging foaming in / to detonate down below / booming with vicarious terror // while high and far out / merging into slate / the open ocean hardly flexes / flat as Lough Ree // midlanders were unready for / such oxymoron’.

The sequence employs Wordsworth’s formula of recollection in tranquility; it is a vision of childhood holidays on the Irish west coast and the emotion is more effectively conveyed, through the distancing. At the same time the reader is wrongfooted by the notion of ‘oxymoron’, as applied to Irish Midlanders. Emotion in Egan’s work is not always recollected in tranquility. Often there’s a sting in the tail: trauma and restlessness also lurk in the past.

In another sequence, ‘Inferences’, the one that closes the book, Egan writes of the personality of Christ: ‘And if everyone panicked in a storm / there you were taking a nap / or out for a walk on the waves/ isn’t there humour in your surprise.’ This is poetry that critiques the self-conscious and the artificial – ‘one more intellectual / without an intellect’. Or: ‘not ever forgetting / you are our now / the unnoticed/ the hands holding the paper the there / even in a daisy that opens and closes / the speck-fly busying by / the architecture of a stray feather / the longing in a face…’

A signature feature of ‘Laptop’ is Egan’s homing in on the eternal in the stuff of everyday life – flowers, skies and beaches, but also in conversations. This trend is sometimes reinforced by an eccentric use of repetition or doubling of phrases, lines or expressions, as if he is holding them up for inspection or else taking pleasure, as we all do, in an echo. The reader soon realizes that a line repeated has a different resonance the second time round. It causes her/him to mull over what has just been said. It is a technique that fosters ‘inscape’ – Hopkins’ term – the interior landscape. It reminds us that we are a mirror of the world around us – both our landscapes or cityscapes, and what we have made of the human world that we have inherited.

It is tempting to label Egan’s poetry as ‘mystical’, as if the medium of poetry itself wasn’t always a way of identifying the memorable in the transitory. In one poem, he speaks of the Swedish pianist Hans Pálsson, a regular performer at the Hopkins Festival. It is poetry about being here and somewhere else as well. He is seen as ‘holding a forgotten coffee / with that expression which / doesn’t belong which belongs / somewhere others have not been…’, while in another poem, a dog that has gone astray is described as having ‘… assumed / the mystique of absence / become more than himself // not up the road / not down / another of those we /discover we love more / after they’re gone’.

I prefer to see Desmond Egan’s poetry as concerned with the intimate world, that of the personal and the interpersonal. It pleads for a resetting of values and priorities. There is the ‘great’ world out there, largely a destructive force. The small world too of our personal relations is also invaded by capitalist values, but we can turn to it as a place where we may perhaps still have something to say. This quest seems to me what this poetry is about. In poem after poem he celebrates, in tautly structured free-verse stanzas ‘whatever is other / the every in any’ (‘Deer in Kildare’). Egan’s work displays an impressive fluency and his voice is an independent one that has ripened over the years.