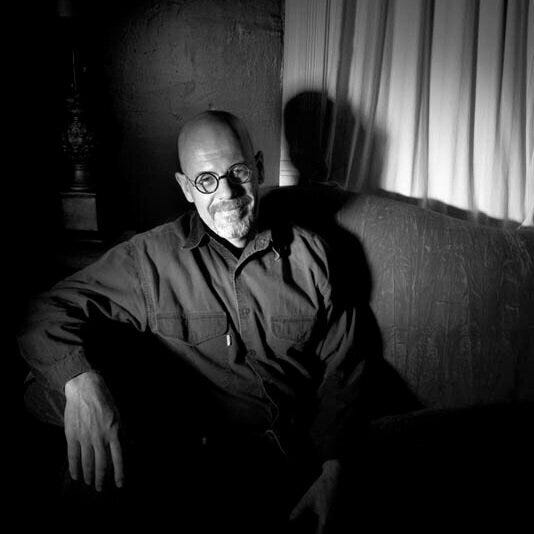

Fiction by Steve Tomasula: "Alien in the Firing Room"

"One of the shadows of the moon seemed to be descending."

“Alien in the Firing Room” is an excerpt from Steve Tomasula’s novel in progress, Our Moon Poem: A Radio Novel, which is about the Apollo 11 Moon landing and how mythmaking becomes history.

Gone. A roar, a trail of smoke, and we’re done.

I sat at my console, gazing out at the empty launch pad where the rocket had stood like a skyscraper, now vanished. As if in a dream. Or rather a fairytale: For the last 9 years, 2.5 million elves had been building a tiny bubble of life atop a metal volcano of plumbing, and instruments, and engines, and controls, each subsystem arising from its own primordial slime. Some five and a half million parts had converged here from all over the country—by ship, by barge, by cargo plane, by truck—to come together as something less built than something that comes into being the way temperature, pressure, dust, and moisture can come together as a snowflake, snowflakes come together as a snow storm, snow storms come together as the Arctic—or the way astronomy, physics, chemistry, the stock market, politics, industries, lobbying, and other forces can come together as….

The rocket.

For the last 6 months—Launch Day Minus 180 Days—that is, T minus 259,200 minutes—Life is very long—26,500 of us had been assembling the rocket, stage by stage, in a hangar designed as a vertical shipyard and so cavernous it could hold all the old cathedrals of Rome. From L Minus 94 Days, we readied the stacked stages as a whole. 587,500 inspection points. We unwobbled wobbly gyros, uncrossed crossed wiring; we replaced explosive bolts that went pffft instead of BOOM!; we fixed a flaw in the Launch Escape Tower; trouble-shot an engine that shut down prematurely; unstuck sticky control knobs, assayed mysterious electrical surges and communication dropouts, debugged reams of computer code, devised workarounds for every conceivable malfunction, and then tested workarounds to the workarounds….

L Minus 17 days and we could all feel time accelerate—Life is so very short—the pyramid of workers whose shoulders we stood on had narrowed by now to the 3,000 of us who conducted a dress rehearsal of the countdown, stressing pipes more pressurized than bombs and super cooled to -423°, loading and then purging five million pounds of fuel, testing abort and destruct systems, monitoring propellant boil-off, check points of tank integrity, skin integrity, yaw control, checks of the LM, cabin environment….

T minus 28 hours—the live countdown: The pyramid of workers had now narrowed to 450 of us, the ones who would actually light the fuse and fire the rocket. We monitored the progress of every system, making sure every valve opened and closed as rehearsed, every electrical current stayed in its wire, every computer meant 11011111 or 00100000 when it said 11011111 or 00100000…

T minus 9 hours: 7 hours ago, at 2:31 a.m., one of the rocket’s 1,202 alarms went off—a sensor detecting a hydrogen leak. On Closed Circuit TVs we could see a white plume of gas streaming from the second stage—less than 3 hours before the astronauts were supposed to board—T minus 2 hours, 45 minutes, 55 seconds.

Astronauts now boarding the transfer van for the trip to the launch pad….

At my post monitoring all the other monitors, I gave special attention to the activity between the team in charge of hydrogen propellant loading and the launch pad—Countdown hold—dispatch Red Team 1 to pad. At the same time, I continued monitoring other channels: Channel 12: a last check of the chlorine content of the water supply in the capsule; Channel 19: Master Alarm reset and all three caution lights are out now. Channel 3: Fuel cell 2 bus feed talkback is gray, verified….

I kept checking the carrier signal for aberrations that could mean that the Russian submarine spotted off shore was trying to interfere with the signal between us and the launch pad as Red Team technicians moved into the tower. A rocket full of 4.5 million pounds of fuel is like a bomb with a blast radius of 3 miles—that’s why I and the other 450 launch monitors in the Firing Room were three and a half miles away, each at a console, each watching an assigned screen, alarm, light, or gauge marked with a red line to indicate a parameter limit. The Key Event Board that had been ticking off each major step was now stuck on HOLD. Everyone was on edge as Red Team 1 rode the elevator up to the 200-foot level. Red Team, re-torque the valve bonnet and the gland bolts, please. Once they had, then came back down, their team leader, 5 rows over from me, typed in the computer commands to resume fueling. Closed Circuit TVs provided multiple angles on the rocket so we could see dozens of points at the same time. Those facing east showed dawn tinting a plume of hydrogen gas a beautiful, pinkish, pale orange. Tightening the bolts hadn’t fixed the leak.

Astronauts have just arrived at pad.

The engineering scrum around Console B18 had grown by the minute, and now included engineers tracing every joint in every line on the hydrogen system as the Red Team raced back up to the 200-foot level. When they poured hot water over the valve by filling their helmets at the emergency shower, it stopped the leak. But Safety wouldn’t let them stand there doing that during fueling. Then one of the engineers cut in: Red Team, try bypassing the replenish valve; we will over-ride the programmed propellant loading sequence, and redirect fueling through main fill valve by manually monitoring its pressure. As the astronauts arrived at the 320-foot level of the tower, the Hydrogen Team resumed loading liquid hydrogen into the rocket, and you could feel relief in the Firing Room as the workaround held.

T minus 2 hours, 9 minutes, 4 seconds and counting….

At my own console, I continued monitoring the systems that monitored the stream of constantly-changing data from the thousands of measurements being taken by the vast network of sensors, relays, circuits, displays, electrical support equipment and computer checks streaming from the rocket’s valves, pressure plates, servos and other components and systems, up through the tower’s umbilical cords, then down through miles of wiring and into the data core shared by our G.E.-635 computer and its identical back-up in the basement.

In the old days, just one system could generate 50 miles of paper readouts, but now it was a live flow and I had the job of monitoring this Niagara of electronic information.

It was my responsibility to understand how all the systems were interacting, and ensure that the routing circuity was delivering the data needed by each of the 449 other engineers in the Firing Room, each monitoring a specific task or subsystem—each subsystem with its own peculiar quirks—and also the Evaluation Room in the basement, which was a kind of backup of the Firing Room. If an engineer flipped a switch and a light that was supposed to come on didn’t, someone had to determine if the fault was in the bulb, the panel, the wiring harness, the software, a sensor, the thing being sensed, or a human—It’s always human error, Dave. An erratic meter could be caused by two relay racks talking past each other or a fifty-nine-cent problem that could blow up the rocket. I had my headset tuned to 21 audio channels at once, adjusting the volume of each up or down so I could be attuned to concerns any of the specific monitors were seeing: D.E.E.-3 is not supporting—the D.E.E.-3 computer that monitored the loading of the rocket’s three-quarter of a million gallons of propellant had stopped reporting—so there was a countdown hold—intermittent sensor reading of hydrogen leaks—another hold—CLGK, power on LVDC/DA per V-33033 and report when complete; Channel 3: …sensor output seems to indicate damage to the anti-slosh baffles in the S-II LOX tank…; Channel 7: …am requesting Channel 181 to troubleshoot a suspected bare line from the storage tank to the mobile launcher saturating at about 40 psig head pressure…; Channel 6: …S-II battery failure—instrument unit guidance timing problems…. It was like riding herd over 50 orchestras that couldn’t hear each other but all had to play within the parameters necessary to create harmony instead of a disaster. I followed along by running a finger down the score—the phone-book thick Launch Manual—focusing on each step as the astronauts went through cabin purge, abort request, and their other final checks.

At T minus 3 minutes, the tempo really accelerated—We are Go—with the master computer taking over hundreds of events, issuing thousands of commands every tenth of a second, actions all up and down the rocket cascading far faster than any human could track. Fifty seconds: Rocket is now on its own internal power. T minus 40 seconds: third stage is completely pressurized. It feels good. T minus 25 seconds… Five, four, three—we are really going to go!—combustion pressure GO…main fuel valves GO…..fuel and LOX rising to maximum chamber pressure…turbopump at full speed—my chair began to rumble—the burning gases rushing out of the rocket reached a million pounds of thrust—I’m givin’ her all she's got, Captain!—but hold-down arms pinned the rocket to earth until they reached 7 million pounds of thrust—two, one—maximum force confirmed!—explosive bolts released the arms…

LIFT-OFF! We have a lift-off, 32 minutes past the hour. Lift-off on Apollo 11!

The building began to vibrate as in an earthquake, but I couldn’t look away from my station. Then I felt the shockwave.

After 8 seconds—it was over: as soon as the rocket cleared the tower, control was passed from our Cape Canaveral Firing Room in Florida to Mission Control in Houston. Only then were we able to look up from our computer screens, switch arrays, meters, indicator lights and paper manuals, turn around and look out the enormous, blast-hardened windows that faced the launch pad, which was now empty, smoldering from the intense heat that had just left it—the rocket’s five engines leaving behind a thundercloud of exhaust.

Bravo! The engineers all around me burst into applause. Bravissimo!

Terrific! Couldn’t have gone better, Roy said, from the console next to mine, and he leaned over to shake hands, which I always appreciated about him, the fact that he always treated me like a regular human.

The tension that had filled the Firing Room just a few minutes ago took on the atmosphere of a nerd party, dancing to the mission marks instead of music coming over the PA:

<beep> Apollo 11, Houston here: You're good at 1 minute… Downrange Velocity 4,000 feet per second…. We confirm inboard cut-off…. Thrust is Go, all engines…..<beep>

Another cheer went up when we heard the callout that meant that the rocket’s guidance system had switched over from the Earth to the stars for its reference points….

Everyone was congratulating each other, calling across the aisles—Live long and prosper!—and I was one of them until the phone on my console started ringing. I ignored it, afraid it might be one of those dirty, anonymous calls I’d sometimes get, and I didn’t want it to spoil the moment. But it kept ringing, so I sprung to my feet, scanned the sea of men around me to see if I could spot one on his own console phone. As soon as I stood, my phone stopped ringing: whoever was calling me was also watching me. But given the celebrations going on throughout the Firing Room, it was impossible to spot anyone abruptly hanging up.

Up in the command fishbowl, I could see Wernher pumping his fist with the Kennedy Space Center Director Dr. Debus, and Karl Sendler, as well as the director of my unit, and some of the other Germans who had designed the first V-2s to lift off in America. I made a mental note to personally congratulate him. And to thank Karl for letting an alien like me be in charge of my part of the launch. It still gave me a rush to think of the day he told me I’d been selected. I had to thank Wernher too. A lot of the men in this room didn’t want an alien amongst them, especially one in charge of communications on such an important launch. But it was Karl who brought my promotion to Wernher. Without hesitation, Wernher had said, Ya, she’s the best instrumentation controller we’ve got.

Maybe he went along so readily because he was a kind of alien as well. Or at least knew what it was to be one. Knew what it was to not be trusted. Knew that an alien would work harder, go to night school after work to finish both a math AND an engineering degree if that’s what it took.

We try harder!

Just to get here she’s had to have more balls than many of the men in this room, I once overheard Wernher explain to one of the men who wasn’t as sure as he and Sendler about my appointment: I took this to be a man’s way of saying that I wouldn’t chicken out if I had to make a call that went against their grain, even if it scrubbed a launch.

I’d thought a lot about that very thing: how I would react if a serious problem came up, partly because of the way I got my promotion: Joe, who had had this seat before me, had been on the job during the dress rehearsal that killed three of our astronauts. Dress-rehearsals always took way longer than the actual launch, so we worked those in shifts. On that day, as the Junior Instrument Controller, I was on the first shift, starting at 6 a.m. Nine hours later, I was exhausted from the concentration, without so much as a bathroom break.

I was headed for the parking lot when an electrical short sparked a fire in the capsule. Because of the shift change, Joe, instead of me, was sitting in this chair, listening to the screams of burning men come through our headset, our control panel ablaze with ALARM lights, the voices on the safety channels frantically yelling, trying to do something—anything!—about the fire raging through the pure oxygen atmosphere of the capsule. Clemmons was yelling for advice on the situation, agonizing over whether he should cut off the oxygen to starve the fire or keep it flowing to feed the astronauts who needed it to live. Up in the tower, Babbitt and Gleaves were burning their hands, trying to get the hatch open. Everyone in the tower was choking in the blinding, toxic smoke. The intensity of the heat melted tubing that began to drip down on them as molten rain, the growing sheets of fire threating to ignite the escape rocket at the top the capsule. And if that happened, it would have incinerated everyone on the tower; it would have exploded the entire rocket, killing everyone, the astronauts, the ground crew, everyone within a three-mile radius….

Of course, there was nothing that Joe, or anyone, could have done. Later, it was determined that the astronauts had died within the first 17 seconds—life is very short—But after that disaster, Joe was one of the guys who couldn’t bring himself to return to the Firing Room….

What would I have done had it been me instead of him in this chair that day? No one can say how they will react in a crisis, but when I remember all the times I was told that aliens shouldn’t be here, that we had no business monitoring the guidance computers, the fire detection system, operational communications, or any of the dozens of systems I have responsibility for, I liked to think that yes, I would have stayed focused on my job, and yes, I would have come back. Maybe for no other reason than to prove that an alien could. Maybe I was as relieved as anyone that today’s launch went as smoothly as it did.

<beep> …Apollo 11, this is Houston. Predicted cut-off at 11 plus 4 2. Over….<beep>

Down here on the floor, a test supervisor was passing out cigars as if we had all birthed a healthy baby, which I guess we had, all 2.5 million of us mothers.

George Mueller, the Director of Manned Space Flight, was now talking to Wernher up in the command fishbowl, a hand on his shoulder, saying something in earnest, and I remembered that though Werhner had no hesitation whatsoever about appointing an alien to the launch team, he had the political savvy to run it by the director first, probably as a way to squash the bud of any discussion against it. It was obvious that he had had to deal with the politics of science his whole life.

Words can’t express the pride I have in all of you, came over the P.A. It was Sam Phillips, Director of the Apollo Program, now on the microphone up in the VIP fishbowl. After saying a few more words of praise and gratitude to all of us engineers on the floor, he asked those of us who were done to stay a while longer because Vice President Agnew was making his way to the Launch Center to address us. In the meantime, they let the Houston-Apollo channel continue to play through the P.A.: …

<beep> Downrange, 1,175 miles….

They unlocked the doors so that staff with lower clearance could come in for Agnew’s address. During launches we were literally locked in the room because if the rocket exploded, the whole place would be treated like a crime scene, and we would be interrogated for any clue that could help investigators piece together what went wrong. Some of the newsmen and photographers who had been taking pictures from the VIP fishbowl were now coming into the Firing Room. One of them made his way to me, and I busied myself at my console—though almost everyone else was done, I still had another 2 hours of work assessing ground performance, lost communication boxes, scorched cables, and other aftereffects for the damage report.

Hey, miss. Miss, he kept calling till I looked up. You don’t have any lipstick you could put on for the camera, do you?

I knew it was going to be something stupid like that, so I just rolled my eyes and went back to work.

Outside, the launch pad smoldered in the distance, out on a marsh where alligators still roamed. Pelicans and other birds that had taken flight at the launch were returning like refugees from deep time—the landscape could have been prehistoric if it weren’t for the fire trucks spraying foam on the concrete that had caught fire. Clouds of rocket exhaust lingered….

As for the rocket itself? Nothing. As if—poof!—a sorcerer had made an elephant disappear. Oddly, Wernher was standing at his window, looking skyward with binoculars to where it had been.

<beep> … Apollo 11, this is Houston. The booster has been configured for orbital coast….

By now the rocket was over the Canary Islands, and as though he realized this, Wernher gave up searching for whatever he was looking for and sat back down in his chair. For a brief moment he was alone, his smile tinged with what seemed to be a shadow of something else, maybe a little nostalgia, or so it seemed to me—or maybe my own mood was causing me to project— I had the odd sense that his expression had something to do with the fact that he had spent an entire life working to create this moment, and then, in a flash of fire and smoke, it was gone—the way the devil disappears in Faust. We all knew about his Faustian bargains. Had they been worth it?

I wonder….

As I went back to work, my thoughts drifted to how we were actually doing not just what Wernher had dreamed about his whole life, but what humans have longed to do as long as there have been humans: Faust willing to trade his soul to rise above the earth; Dante’s trip to the moon where he learns that its dark spots are as the shadow of memory is to experience, or the shadow of a sundial is to time, and time is to the eternity glimpsed a thousand years earlier by the Roman general Scipio, looking back to Earth from space and seeing how all the Earth was no more than a mote of dust in a shaft of cosmic light.

<beep> … Vanguard L.O.S. at One five three five. A.O.S. Canaries at one six three zero. <beep>

Then there were those stories I so loved when I was young, especially those of aliens coming to earth to mingle with humans. My favorite was that ancient Japanese tale of the old bamboo cutter who found inside a shoot a thumb-sized newborn, glowing the pale white of a moonrise.

The old bamboo cutter and his wife raised her as if she was the child they never had, and loved her more dearly than life itself. As month after month passed, she grew into a radiant young woman, able to play the Koto so ethereally that many men fell in love with her, though she would have none of them, not even the emperor.

One night, her aged parents discovered her weeping in their moonlit garden. When they asked her why, she told them that she had grown into the knowledge that she was destined to return home.

But here is your home! they told her.

Tearfully, she told them that her true home was the moon. There, her soul used to gaze back at Earth, a beautiful, blue, watery globe in the dry moon’s night. So intense was her longing for Earth that she began to float, drawn through space and time to their world, her memories fading as did her past, till she was reborn as the tiny infant they found in the bamboo shoot. But as she began to age again, the memories of deep time that her other self had known had begun to return to her, and they began to make her realize why Earth was so precious: unlike the moon, which was eternal, all life on Earth was as transitory as the morning dew, no matter how much one loved it, or was loved by others….

Her parents were grief-stricken by the thought of their daughter leaving them, and at such a young age. They promised to defend her, to place themselves between her and the emissaries from the moon she felt were coming to take her back. The emperor, who thought of her as a national treasure, sent his entire army to protect her. Just as we would waste away if all we did was long for the moon, she began to fade. They’re coming, she informed her parents, growing weaker. A few nights later, when her mother leaned close to better hear, she whispered, Tonight.

All the servants and soldiers were put on alert: the most powerful army in the world kept guard, poised for combat. About midnight, when the full moon was high in the sky, a sentry sounded the alarm: Look! There!

One of the shadows of the moon seemed to be descending. As they watched, it seemed to transform into a cloud that had the shape of a porcelain saucer. With dread they realized that it was coming right at them, growing larger and larger. The cloud drew close enough for them to see moon men and women riding on it, richly dressed, though expressionless and pale as the dead.

A thousand archers released their arrows. But the arrows only turned into a hail of flowers. Then the soldiers, the parents, all the servants—everyone—fell into a deep sleep, helpless. When they awoke, the girl was gone, and dawn was tinting the clouds a beautiful, pink-orange.

<beep>…Apollo 11, this is Houston. Thrust is good. Everything's still looking good. <beep>…

###