“You got to be a spirit, and the spirit will not descend without a song.”

Many of us were taken aback watching the 1998 Warren Beatty vehicle Bulworth, not simply by the sheer awfulness of the movie, but by the walk-ons by poet Amiri Baraka, credited as the character “Rastaman,” despite the fact that there was nothing remotely connected with Rasta in the character’s costuming. Senator Jay Bulworth is several times accosted by a homeless man dressed in brown coat and wearing a flat hat over a knit cap, who warns the Senator about the ghosts who stole the ancestors from Africa and who are clearly (to Rastaman, at any rate) still circulating among America’s powerful to this day. “You got to be a spirit,” advises Baraka’s avatar in this holy mess of a movie.

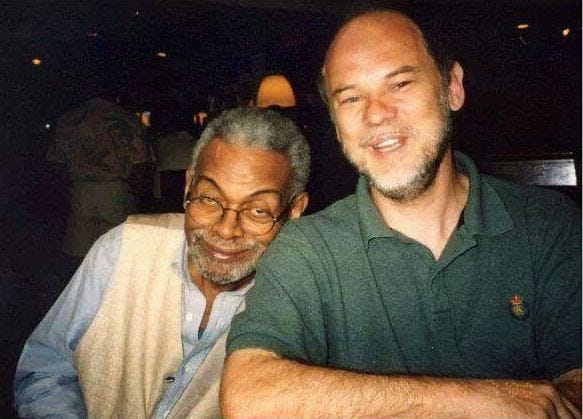

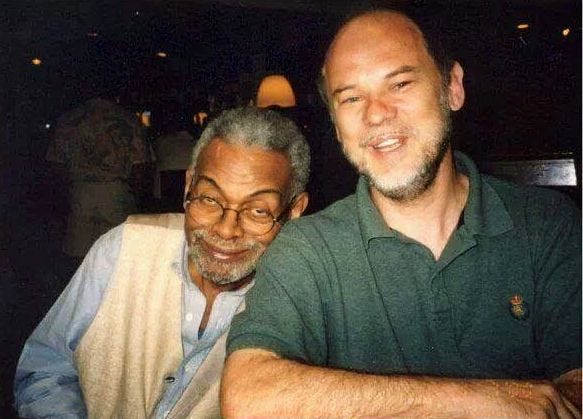

Some time later, as we sat around a dinner table in Boulder, my wife, film scholar Anna Everett, asked Amiri Baraka about his appearance in the film. Baraka detailed the initial phone calls from Beatty, how Beatty had sent him a provisional script, and how Baraka had made a few suggestions. Then, to use Baraka’s word, the director took the script and “Warrenized” it. One remarkable thing about Baraka’s spectral appearance in the film is that while he is instantly recognizable, and his distinctive voice is heard uttering lines that could be coming from poems of his, on the sartorial side it would be hard to imagine a less Baraka mode of dress. His character is supposed to present as a homeless nut case who, seemingly inadvertently, speaks truth to wannabe power, but there is always that moment of cognitive dissonance when a well-known real person wanders into a fictional film dressed so unlike himself.

Twenty-first century students are often surprised to see period photographs in which the Beat poets and their New York School brethren are seen duly suited and wearing ties. By the later 1960's, Baraka’s move into cultural nationalism had been accompanied by a dramatic change in appearance, the suits and ties of the “Beat Period” now replaced with dashikis and African accoutrements.

By the time I met Baraka, he had left cultural nationalism in the dust. Experience had taught him that, as necessary as the cultural turn may have been, political power does not grow out of the sleeve of a dashiki. The first time I attended one of his readings, I went fully expecting to see the self-styled Imamu Ameer Baraka who had authored Black Magic Poetry. Instead, while he was the same poet, I witnessed the author of Hard Facts and Poems for the Advanced, now wearing a Mao jacket and hat, abandoning references to Kawaida ideology and instead peppering his commentary with references to Lenin, whose ideology he had previously violently rejected. And yes, the evening had more than a fair share of agit prop verse, in which I had little interest (aside from trying to figure out just what sort of Marxist he had become). But there were also many moments like this:

We are picked, and pick ourselves, for what we do and are

We make our eyes stretch and fill our bones, pack our heads

with what we want to pack them with . . .

*

I next met with Amiri Baraka in the classroom. By then I was a doctoral student at George Washington University, and one year he was the visiting writer. I enrolled in his course in African American literature. The following year I was in charge of arrangements for a return visit by Baraka, who had agreed to come and do a reading as a fund raiser for the campus writer’s group. I had booked an Amtrak ticket for him and sent him a $100 honorarium, considerably less than his usual reading fee, to put it mildly. Come the day, a good crowd showed up, but as of a half hour before the reading we’d had no sight of Baraka. Memories of infamous no-shows filled our heads, but then we saw him walking up 21st Street, NW, lugging his ever-present cache of chapbooks and copies of his Unity and Struggle newspaper. Baraka had managed to miss his scheduled train, but then, at his own expense, had hopped on a flight out of Newark, landed at National Airport and taken public transport the rest of the way. He had also missed any semblance of a meal that day, so my classmate Richard Flynn and I took him up to the top floor of the Marvin Center to grab a quick sandwich. The audience stuck! I shortened the intro a bit due to the late start and turned things over to Baraka. Many in the hall came expecting the roaring lion of rumor, and there was plenty of that to come. But first, settling the mass of manuscripts he pulled from his briefcase on the podium, he began quietly intoning “Dead things . . . “ Some of the poetry from that era was retrospective, reviewing the years and actions that had formed the mythology of the Black Nationalist poet:

An old story–the world–old now for us who was once a young stormy buck railing railing

even the tone sounding inside for the change of things that we never knew . . .

Other poems recalled his literary youth:

I’ll give you a silver dollar

if you’ll learn The Creation.

Why eyes. Bug eyes. My mother

had me saying The Gettysburg Address

in a boyscout suit.

He never did, the poem lets us know, earn that silver dollar by committing James Weldon Johnsons’s canonic poem to memory, and come to think of it, I never once saw him recite any of his own work from memory. Even the hard core Marxist-inflected work often took a lyric turn:

communist sparrows gnawing on a fire escape

together in bread lines flying off to the next low house

This was not your daddy’s political poetry.

Again, as Baraka worked through the poetry he read that day, he provided many asides, and did indeed bob and weave like a boxer, shouting like a Baptist minister coming to the climax of his Sunday sermon and firing up the choir, urging his audience to commit to Marxist revolutionary politics. But it wasn’t just the politics that had changed. While he had published poetry, essays, and music criticism with Grove Press, Morrow and other commercial houses, now those home-made chapbooks he always brought to readings had become the main point of publication for most of his verse. As he said, accurately, on more than one occasion, it was easier for him to get published with “hate whitey” than with “hate capitalism.”

That mixture of Projective Verse aesthetics and political propaganda I had seen from the Baraka of his middle years came to characterize his appearances right up through his wandering into Bulworth and up to his final days. I was to find myself with him often over the years, sometimes introducing him at readings, other times speaking at conferences where he was also on the agenda. Whether introducing him, or speaking of his work in front of him, it was always an odd sensation, delivering my sense of the work as the author himself—who used to grade my graduate papers—was right there in front of me. And observing his aging brought home all too spectacularly my own. It came home to me that when I first bought a copy of The Dead Lecturer, at age 14, Baraka himself was but thirty years old. When I entered his African American literature course as a grad student, he was just in his mid-forties. Time did nothing to smooth the rough edges of his ferocity, nor did it lessen the intensity of his more lyric poetry.

*

A number of Baraka scholars and colleagues once gathered at Howard University for a day dedicated to his work. That evening there was a benefit dinner, raising funds for a possible chair endowed in the name of Baraka’s own college teacher, Sterling Brown. Max Roach’s drums were set up on the stage, so we knew we were about to witness something momentous. When it came time for Roach to take the stage, I feared he might not make it up from his table; he appeared frail and aged. But once he sat down on his drummer’s throne, he was like a kid banging on his first set of drums in his parents’ basement, and Roach proceeded to deliver a veritable master class in solo drumming. Then he called Baraka to the microphone. They had not rehearsed a program, but the two of them had performed in tandem in the past. Max Roach was a decade older than Baraka, and yet the two of them would have put most performance and slam poets to shame on that night in D.C.

I was to see a similar on-stage transformation one of the last times we were together. The two of us were on a program at Georgetown University built around revisiting the arts of the Civil Rights era, hosted by, among others, poet Mark McMorris. Sitting beside Baraka I spotted the tiny hearing aids now in his ears. Even in youth, he had been a bit stoop-shouldered, but now, always a short man, he had diminished in size and strength. He and his wife, Amina, had been in a bad car accident some years before, and he clearly still labored under the effects of his injuries. Like Max Roach, he was tentative walking up the steps to the podium. Also like Roach, once he was deeply into the poetry he was the raging militant of his youth. Still, there was always that lyricism amidst the roar of his politics.

Where ever something breathes

Heart beating the rise and fall

Of mountains, the waves upon the sky

Of seas, the terror is our ignorance . . .

Bulworth gives Baraka the film’s last words. Beatty’s politician character having been assassinated, the final scene has Baraka’s Rastaman leaning towards the camera, directly addressing the audience, imploring us, as he’d earlier cautioned Bulworth, “don’t be no ghost.” The message remains, we need a spirit and a spirit requires song. Spectral as ever, he then turns his back to the camera and walks slowly away down the sidewalk by Cedars Sinai Hospital. Rastaman is clearly intended as a premonitory trickster figure. Such was Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones through all his changes.