Cassandra Atherton: Alice in Wonderland in Japan

“The first dollars used in postwar Japan are on women’s bodies.”

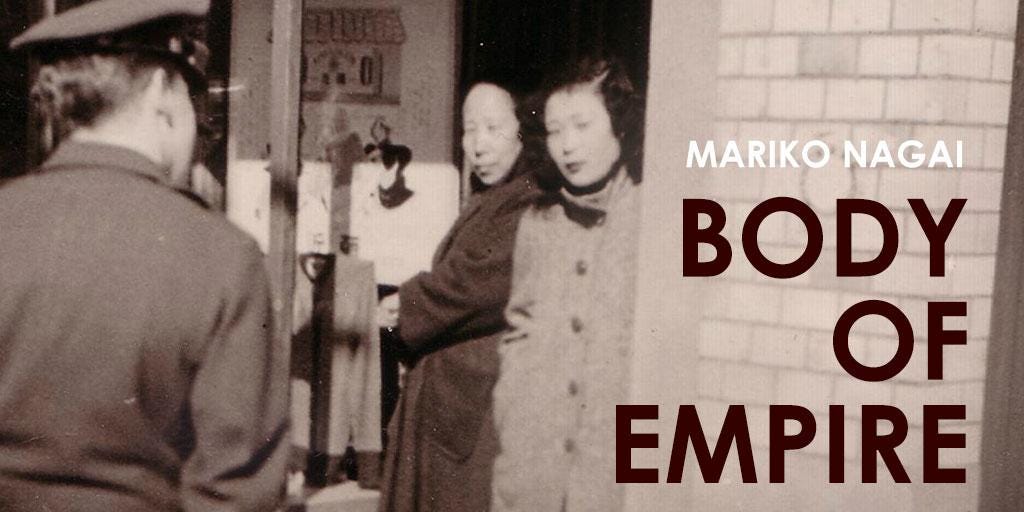

My first dispatch from south of the equator was inspired by a package I recently received from Mariko Nagai. It was wrapped in innocuous brown paper with Alice in Wonderland sticky tape, which belied its contents—a copy of an extraordinary book of prose and prose poetry. Titled Body of Empire, it illuminates the experiences of (primarily) Japanese women in WW II, focusing on the relationship between the body and imperial power. Nagai writes:

“The first dollars used in postwar Japan are on women’s bodies.”

Her book includes photographs, testimony, journalism and many other historical documents. There are also a whopping 530 notes, which are an incredible feature of the book. It makes me think about how prose poetry may be structured and layered, like a creative form of an archive.

Tokyo lies in ruins. Bombed-out people hurriedly make shacks out of lumbers from their neighbors’ burned-down houses. Children are shipped back from their evacuations, only to find themselves orphans. Girls working on ammunition factories find out that their families have all died, or that there is no way to go home because railroad tracks have all been bombed or made useless. They walked about as ghosts, half here, half there, their future unknowable and their present desperate. (from Body of Empire)

Body of Empire dwells in liminal and abject spaces. It’s visual and confronting on the atrocities of war, but more importantly it asks readers to focus on women’s experiences of colonialism. I’ll never forget moments such as:

“She says that whenever a man was on top of her, she would close her eyes and imagine choking him to death.”

I travel to Japan almost every year, sometimes for work and sometimes for a holiday. It’s not too far from Australia—a direct flight from Melbourne will get you there in just over ten hours. Japan is also in roughly the same time zone as Australia, so I can travel there without getting jetlag. There are fascinating poetry scenes in Japan but you generally need an introduction to be part of them. Many Westerners talk about Japanese poetry in terms of haiku or renga, but contemporary Japanese poetry is also about free verse and experimentation. And women poets in Japan are very slowly starting to get the recognition they deserve, though they’re still vastly unrepresented in publications and awards.

I got in touch with Mariko for the first time after reading Irradiated Cities, a book of prose poetry and photographs charting nuclear catastrophe in Japan. The writing in this book is nothing like I’ve seen before and it uses colons between phrases and clauses to separate and unite fragments. It’s recently been made available to read here, as Open access.

The colons frequently signal conclusions that never really conclude, and fractured sentences convey a sense of the ruptured, post-atomic world. Similarly, snatches of dialogue rather than complete conversations convey the shattering of families, homes and communities. Mariko captures conversations of hope and despair:

calling : have you seen … ? : have you seen my husband? he works here : my children went to school here : floors of buildings covered with the wounded & the dead : nights do not come : the sky never darkens : the white nights alight with fire from the ground : have you seen …? :

[…]

Searchers walk amid the dead & the dying & the city that was but no longer, looking for someone, anything familiar : a name tag : a rumor of sighting : anything & everything : they walk : they walk all day : they keep scratching messages : it is another hot day in August : it is still a clear day : they do not know that their bodies now carry a bomb inside : a ticking bomb :

The reverberations of the last line with its concluding colon seem to go on forever …

I visited the Radiation Effects Research Foundation in Hiroshima. It was established in 1975 to study the effects of radiation exposure on survivors and was then called the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission. Notwithstanding its valuable research, it has been criticised for its treatment of hibakusha (people affected by exposure to radioactivity). This “ticking bomb” inside survivors was stigmatising and, in the early days, some felt they were treated as experiments.

Endnotes and footnotes in poetry collections are becoming more common. Perhaps this is because of plagiarism accusations against some poets and the advent of AI. However, the “endnotes” in Body of Empire are much more than a record of the book’s sources. They’re powerful mini-narratives in their own right; snapshots of history, and may be read independently as evocations of people’s lives. Mariko talked about poetry and archives at the Poetry on the Move Festival in Canberra, Australia in 2022. You can see some of that here.

Alice in Wonderland holds special significance in Japan, where Lewis Carroll is the best-selling English-language author of all time. I’ve been to the Alice in Wonderland Restaurant in Shinjuku where they have pages from the novel papering the walls. I’ve visited the giftshop, Alice on Wednesday in Harajuku where I ducked through a tiny door to enter. Both the 80th anniversary of the atomic bomb being dropped on Hiroshima and the 160th anniversary of the publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland occur this year: 2025.

Alice on Wednesday, Harajuku